This document is part of a series on Factory2.

Modelling Dependencies

As per our order of execution analysis in the overview document, let’s take on Dep Chain (#7) first. We have a perfect store for this data, ready to be filled: PDC, the product-definition center.

PDC can hold many different kinds of data, but we’re only interested in a subset of its endpoints for this project. The release-components and the release-component-relationships endpoints.

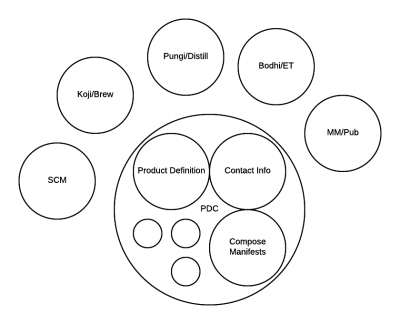

(As an aside, the variety of other endpoints in PDC has led to much confusion, so its worth taking a moment to clarify. Housing the “Product Definition” data is only one small part of PDC’s design. It has a very effective endpoint for storing the manifests of completed composes (in the well-defined productmd format). It also has endpoints for storing contact information for various components (pkgdb plays that same role in Fedora). Very important for PnT Devops, it has tables to define a product before any parts of that product have been built. The goal there is to allow Product Management to submit a definition for a new product, and to in turn have all our other tools simply query PDC and follow suit. None of that has anything to do with modelling a dependency chain. It is only to point out that PDC does more than just define a product. It would be better named something like metadataDB -- the generic metadata store for our infrastructure.)

Some of the metadata types in PDC are new, unique kinds of data for which we have no other home. Inside Red Hat (where we don't have pkgdb), we currently have nowhere to reliably query for per-component contact information - that’s a unique PDC endpoint. We have nowhere to define hypothetical products - that’s a unique PDC endpoint. Being the only copy, they are authoritative.

Other PDC endpoints are queryable caches of data that really live elsewhere. The compose manifests in PDC are really just copies of the manifests stored on-disk in the compose tree. For these endpoints only, PDC acts like a data mart -- a non-authoritative cache designed for convenient access.

The release-components and release-component-relationships tables are just that: non-authoritative caches of the real relationship data which lives in dist-git, and in some cases in built components.

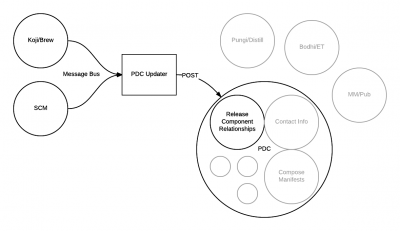

To maintain our model of the dependency graph, we’ll extend the pdc-updater service written for Fedora Infrastructure to update the release-component relationship endpoints.

People new to the RPM world frequently conclude that an RPM’s dependencies can be derived from its specfile. This is not quite true. The context in which an RPM is built can affect the values of various macros and can radically alter the output. Accordingly, it only makes sense to model the dependencies of built RPM components. Each completed build will publish to the bus, which will trigger PDC updater, which will in turn POST its dependency information to PDC.

Modules, on the other hand, we expect will carry static manifests of their dependencies. Therefore, we’ll be able to extract a model of their dependencies directly as their definitions change in dist-git.

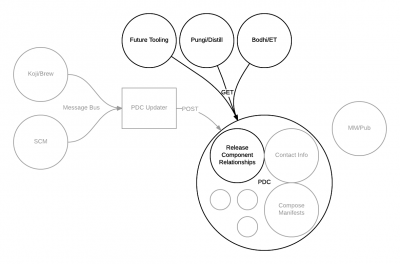

Once modelled in PDC, our dependency graph can be used in a variety of ways.

- We’ll build future tooling to automate rebuilds of components. Such systems will need to know dependencies in order to know just what to build next.

- We’ll build future tooling to provide analytics and insights on our product dependencies. If we abandon component X, what offerings are affected? If we conjecture a new offering Y, composed of modules A, B, and C, what components are involved?

- Our gating and composition tools can get smarter. We’ll be able to introspect compound entities (like modules, containers, etc..) while remaining agnostic to content.

We should be able to bring this problem to solution iteratively. There’s no need to solve every dependency type at once, but instead we can enhance pdc-updater as we identify new needs with a corresponding gap in PDC dependency data.